11 KiB

senior-design

Code and analysis in support of aerodynamics on senior design project. Most recent last modified date was April 17, 2010 at 7:53 PM

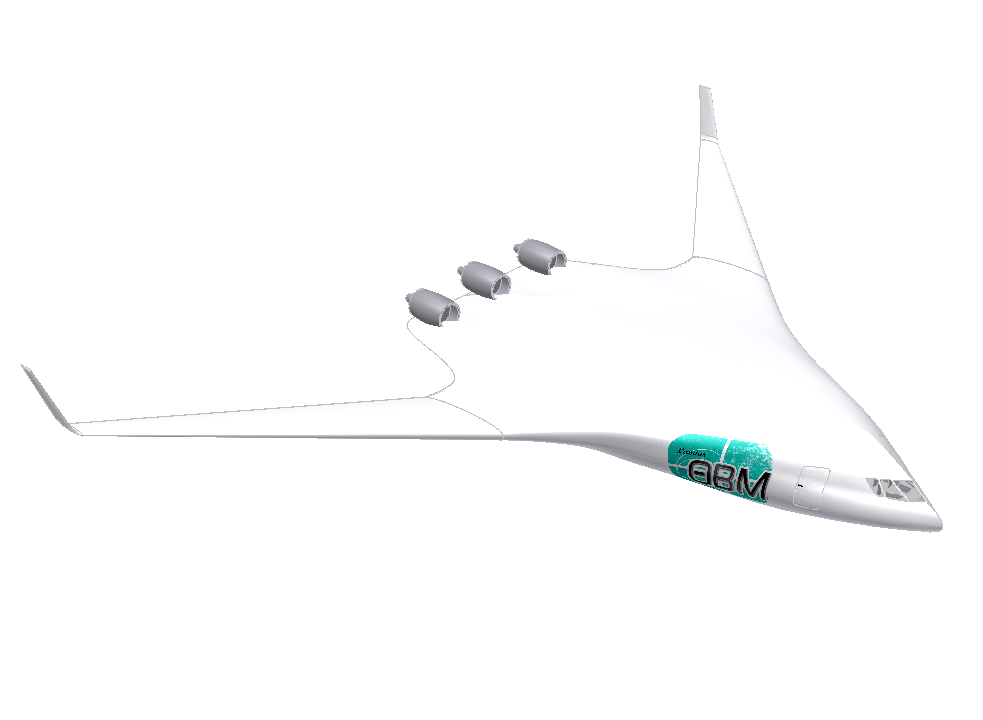

2009-2010 AIAA Undergraduate Team Aircraft Design Competition Concept

April 12, 2010

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The θBMaero Lamiar is an airliner designed with the environment in mind. An environmentally friendly airfcraft is more fuel efficient, emits less pollutants, and makes less noise. The Lamiar meets and exceeds these challenges. Utilizing the blending wing concept and a multidisciplinary design process, the Lamiar has been designed to satisify these goals without sacrificing capacity or range. The geared turbo fan engine has been engineered to run up to 10% quieter, burn 20% less fuel and run on renewable organic fuels as well as traditional fuel. Improved aerodynamics give the Lamiar a boost of 25% in lift-to-drag ratio in comparison to the Boeing 737. All this has been done while keeping the airplane stable, structurally sound, and the passenger and luggage capacity of current airliners. Requirements of the American Institute for Aeronautics and Astronautic’s request for proposal as well as requirements based on the National Aeronautics Research and Development Challenges have been met. The Lamiar represents the future of civil transport.

AERODYNAMICS (ASC)

Introduction

The Lamiar was designed with environmentally friendliness in mind. In conjuction with the explicit L/D ratio requirement from the RFP more efficient aerodynamics were needed. After research on the topic, it was agreed that the best way to meet this requirement would be to design a BWB. Research shows that the BWB offers favorable aerodynamic benefits. (Qin, 2004) The initial sizing and constraint analysis provided by performance gave a starting point to the aerodynamic design, and as design progressed, the values become more refined. Table 4.1 shows the performance values that governed the aerodynamic design and the values attained at current design.

Table: Constraint Analysis Initial Figures

| Preliminary Design | Final Design | |

|---|---|---|

| Wing Loading (lb/ft2) | 36.4 | 33.4 |

| Weight (lb) | 160000 | 173000 |

| Wing Area (ft2) | 4400 | 5190 |

Planform Design

Although the Silent Aircraft was used as inspiration, the Silent Aircraft made design choices that were not specific for this RFP. For instance, the wing sweep on the silent aircraft is about 38 deg. This is because it is optimized for most lift; however L/D is maximized at 42 deg. Since our design is keyed on L/D ratio, it makes more sense to sweep to 42 deg (Siouris, 2007).

The planform was designed based on a trade study of various BWB configurations. XFLR5 was used extensively during aerodynamic analysis as it proved an easy tool for rapid modeling using airfoil data. A MATLAB code was written to evaluate geometric values and using aerodynamic parameters calculated from XFLR5, the configurations were assessed. The preliminary design had problems in stability, so consideration was made to move the wing farther forward as to bring the neutral point farther forward while keeping the wing sweep around 42 deg. In total, approximately 10 iterations were made in this phase of the design study. Fig. 4.1 shows the L/D of several different candidate planforms. It was decided that the best iteration was FDR005 and was used as the basis for the next step in the planform design.

Figure: Planform design comparison of L/D.

After figuring out a wing placement and general shape, another trade study concerning fitting the passenger compartment was conducted. Another MATLAB code was written to give lines of constant heights of 13.25 ft and 10.5 ft (denoted by a solid and dotted red line in Fig. 4.2 respectively) to accommodate passengers (denoted by a blue line in Fig. 4.2). The diameters of each cylindrical component of the pressurized cabin were 13.25 ft and 10.5 ft respectively. Fitting was achieved by varying the airfoil selection, and tweaking dimensions. During this secondary design study, approximately 10 more iterations were performed until the suitable candidate FDR020 was reached. Fig. 4.3 shows a more detailed plot with an isometric view to show the amount of height available inside the aircraft.

| Wingspan (ft) | 160 |

|---|---|

| Wing Area (ft2) | 5200 |

| Wing Sweep (deg) | 42 |

| Length (ft) | 98 |

| Centerbody Width (ft) | 58 |

| Mean Aerodynamic Chord (ft) | 60 |

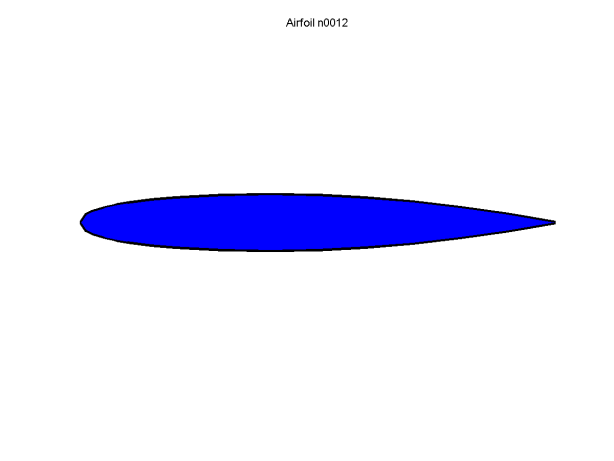

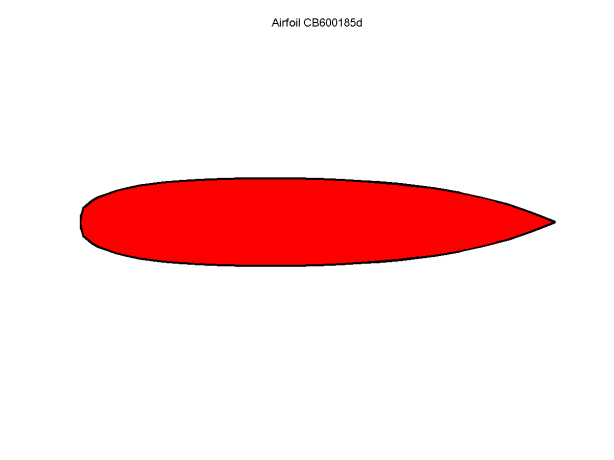

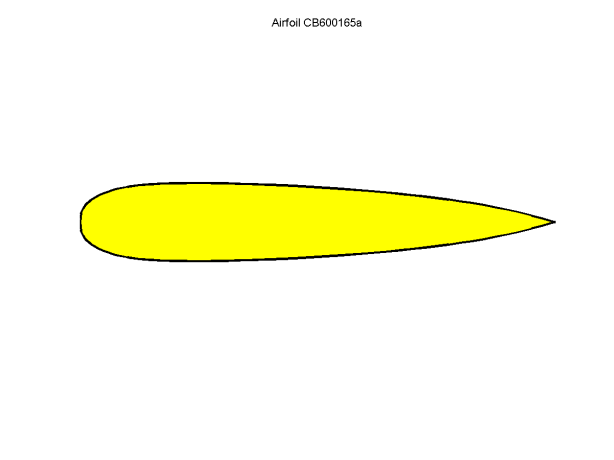

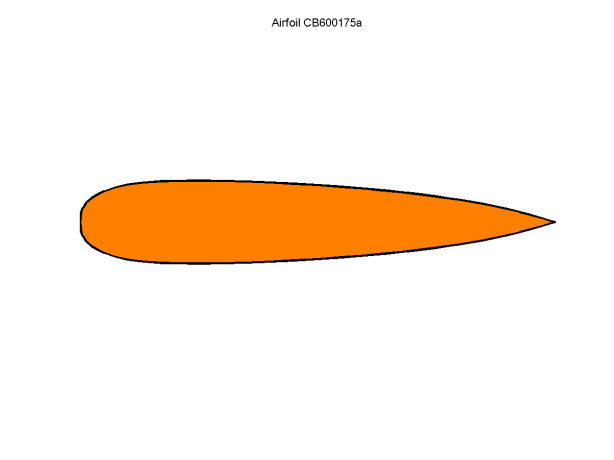

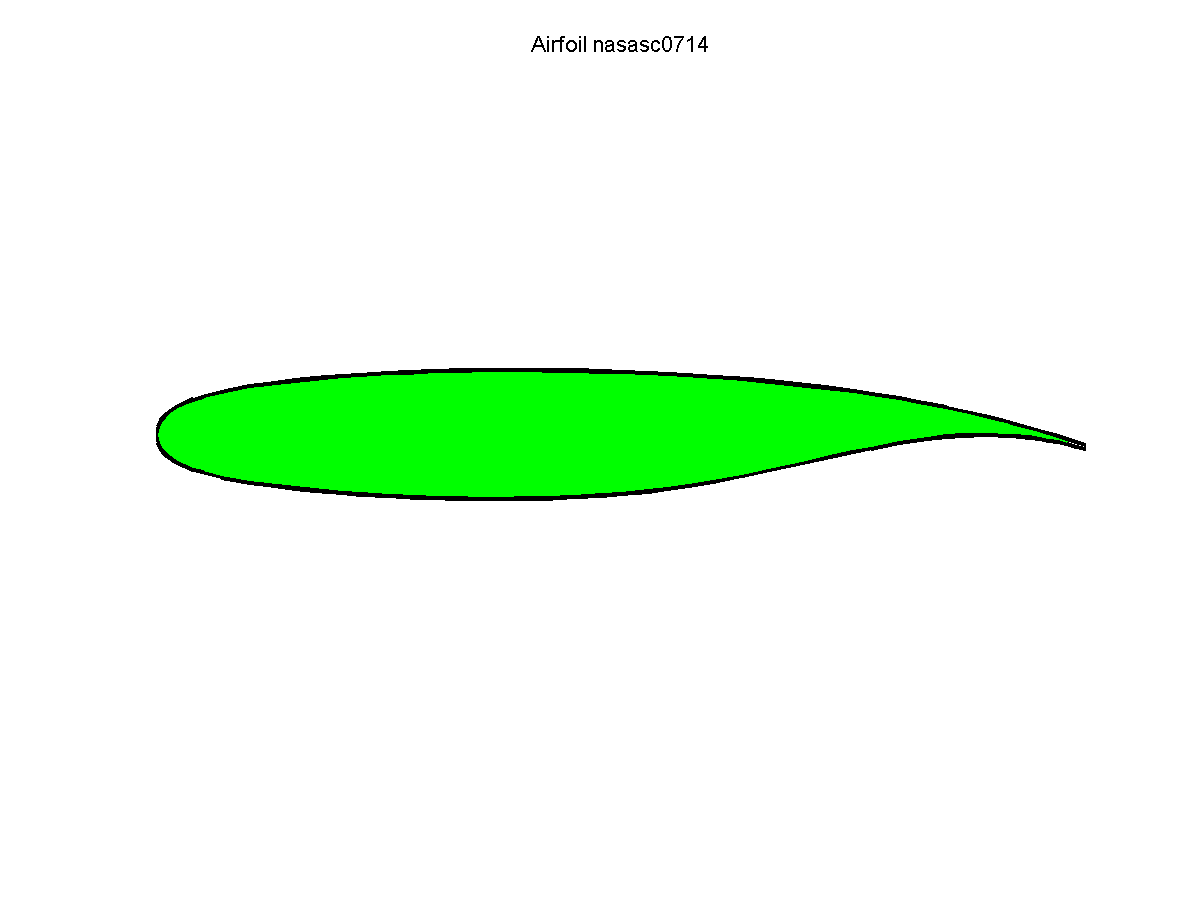

Airfoil Selection

In order to find an airfoil that satisfies a low drag condition at cruise, research was devoted to finding transonic, or more specifically, supercritical airfoils. Several supercritical airfoils were tested. The next airfoil needed was for the centerbody. The centerbody airfoil poses a unique problem; an adequate thickness is needed to fit the passenger cabin. A NASA supercritical symmetrical airfoil was modified the airfoil to accompany passengers. The modified airfoils, listed in Fig. 4 were customized to allow necessary thicknesses were the cabin is located. This meant an 18.5%, 17.5%, and 16.5% thickness airfoil along the span respectively with varying chordwise thickness locations. The outboard wing was chosen as the supercritical airfoil NASA SC (2)-0714. Toward the tip, the symmetric airfoil NACA-012 was used to prevent tip stall and provide a more ideal CL distribution which is discuss further in Section 4.5. As shown in the Table 4.3, the efficiency is high. This is due to the BWB’s inherent better wing aerodynamics and the winglets.

| CLα | .037 (1/deg) |

|---|---|

| αL=0 | -2.3 deg |

| Cm0 | -.0369 |

| e | .98 |

Drag analysis

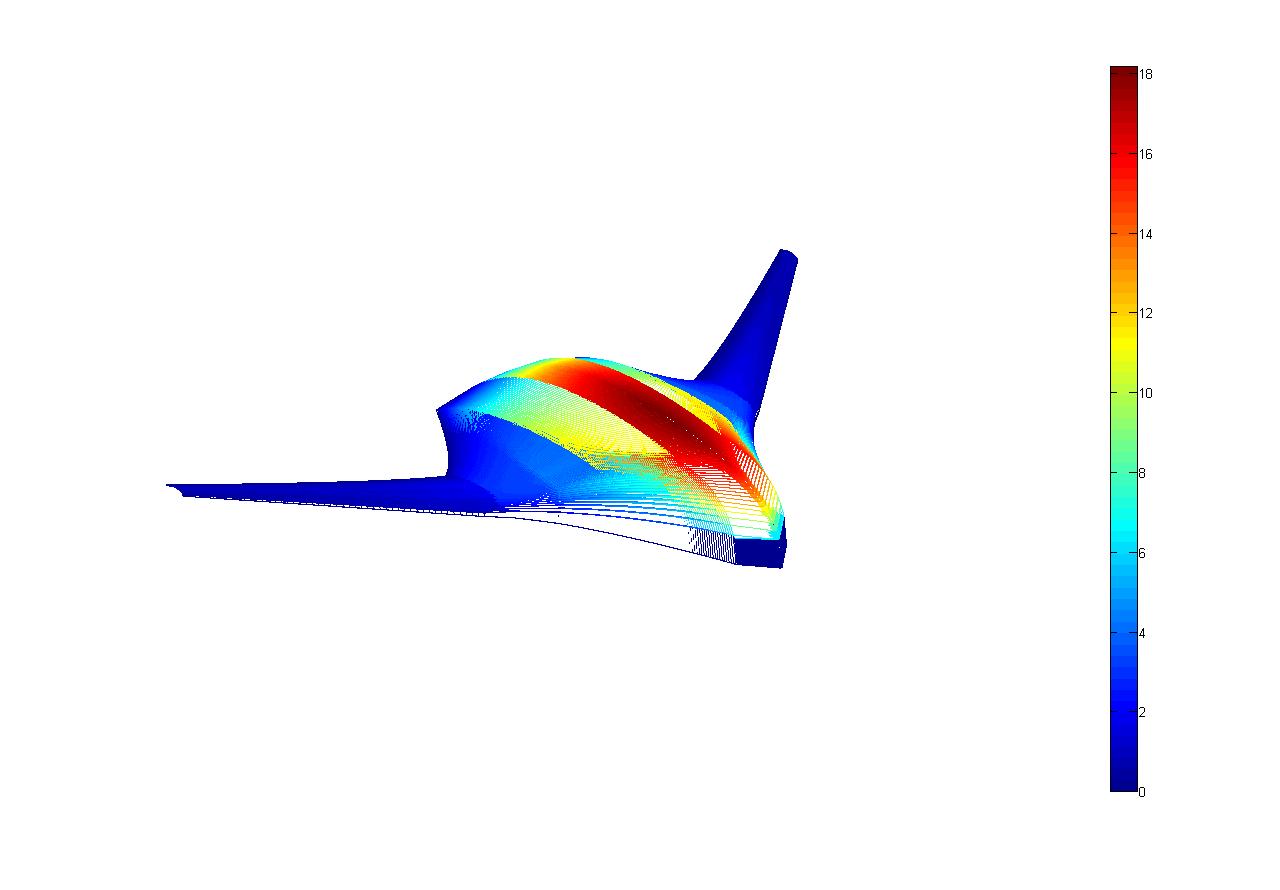

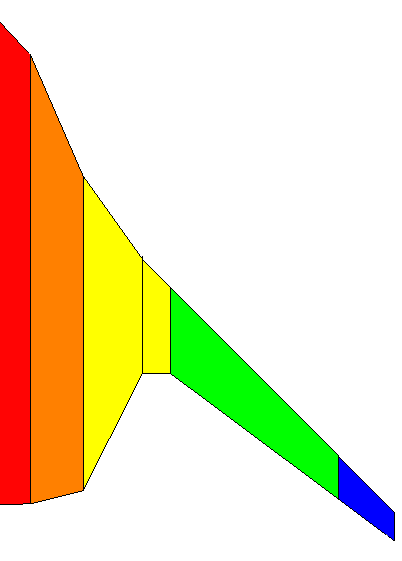

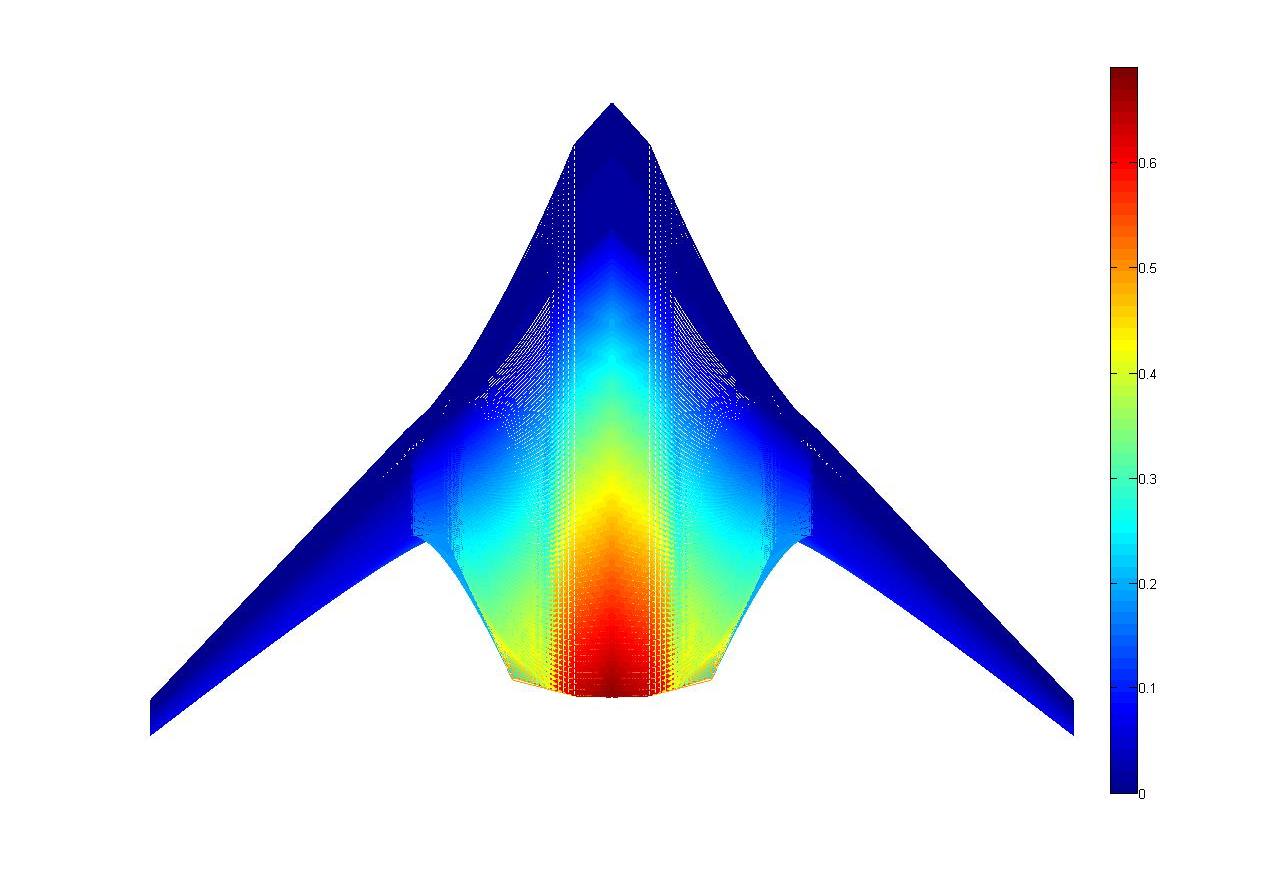

The next analysis was the drag. For the BWB, most zero-lift drag comes from skin friction drag. There is little interference drag on account of the blended fuselage with the wing. Since the Lamiar travels at transonic speeds, it was important to take into account transition effects. A flat plate estimate was used for the discretized wing span. It was estimated that the flow would be laminar for about 20% laminar over the length of the fuselage and wing and allowing for the 20% addition in laminar flow specified the RFP, it was estimated that over the wing the flow would be approximately laminar for 45% of the chord. Research engineers at the LaRC estimate that even as high as 50% is reasonable (Braslow, 1999). Laminar flow control can be attained from leading edge suction through microperforation (Braslow, 1999). The power required for suction was added by the propulsion specialist. Fig. 4.6 shows the calculated boundary layer thickness and that the largest thickness occurs somewhat expectedly along the centerline (McCormick, 1995). The center engine will ingest. Ingesting the boundary layer where it is the thickest is ideal for aerodynamics. Due to boundary layer ingestion caused by the engine placement, it was estimated during performance analysis that a drag reduction of 5.7% can be achieved; however, ingesting the boundary layer is generally bad for the engine and this will be addressed further in Section 6.2.

| CD fuselage | .0051 |

|---|---|

| CD wing | .0014 |

| CD engine | .00050 |

| CD landing gear | .0026 |

| CD0 takeoff | .0096 |

The drag polar can be calculated from the CD0 and the induced drag. Fig. 4.7 shows the drag polar evaluated at takeoff.

Figure: Drag polar at cruise.

The CL values are known at each segment from flight conditions and wing area. Using CLα data, it was determined that the appropriate angle of attack for cruise would 1.74 deg, and to ensure a level cabin during cruise, 1.75 deg is set as the incidence angle. The CL at take-off is constrained by take-off distance requirements provided by performance. After taking into account ground effects, the angle of attack required at takeoff was calculated to be 4.5 deg. To achieve this angle of attack it is necessary for the landing gear to be designed in a way to add 2.75 deg to the incidence angle. The values for various mission segments are listed in Table 4.5.

| Takeoff | Cruise | Loiter | Landing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL | .48 | .149 | .281 | .48 |

| CD | .027 | .00681 | .0108 | .020 |

| α (deg) | 4.50 | 1.75 | 5.30 | 4.20 |

| L/D | 16.7 | 21.9 | 25.9 | 20.1 |

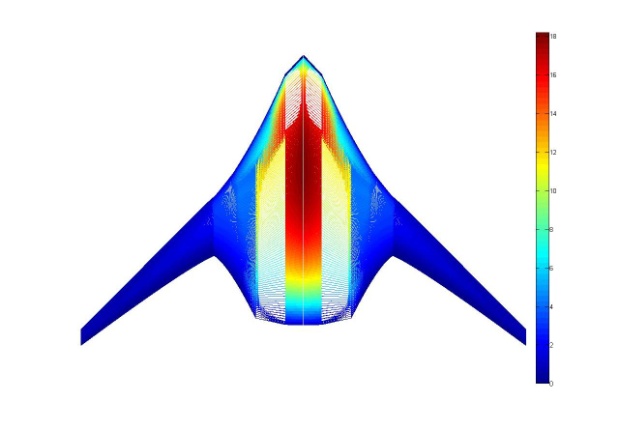

Load Distribution

Although not valid for lift and drag calculation, XFLR5 was useful for finding lift distribution. Fig. 4.8 shows the CL distribution at cruise which was given to the structures specialist to analyze. According to a study done at the University of Sheffield in the UK, the best lift distribution is a medium between elliptical and triangular. This is because an elliptical distribution gives the lowest induced drag while a triangular distribution gives a lower wave drag. At cruise speeds, wave drag should be considered. The lift distribution to be targeted will is represented by the dotted line in Fig. 4.8 (Qin, 2005). An effort was made to match the lift distribution of the Lamiar to this distribution by varying wing twist and adding a symmetric airfoil at the tip. A twist of 5 degrees near the tip and 2.5 degrees at the tip was found to help bring the Lamiar’s distribution close to the ideal. To prevent tip stall the maximum CL along the span was made to be at about 35% span, ensuring that the wing will stall inward first rather than at the tips.

Conclusion

It can be seen that the L/D requirement was met. Aerodynamically, the Lamiar will be more efficient thanks to the utilization of novel configuration optimization and laminar flow technology as specified by the RFP and the National Aeronautics Research and Development Challenges. An L/D of about 22 can be achieved during cruise; this is an improvement over the current generation Boeing 737 which has an approximate lift-to-drag of 17 at cruise. The L/D improvement was achieved thanks to the BWB concept, boundary layer ingestion, and laminar flow control. These achievements help to make the Lamiar an environmentally friendly plane by lowering drag and in turn the thrust required.